by A-B-E

I facilitated the second workshop of my Spoken Word Poetry residency with my young people in Queens yesterday. The residency serves a small group of high school teenagers, grades 10 – 12.

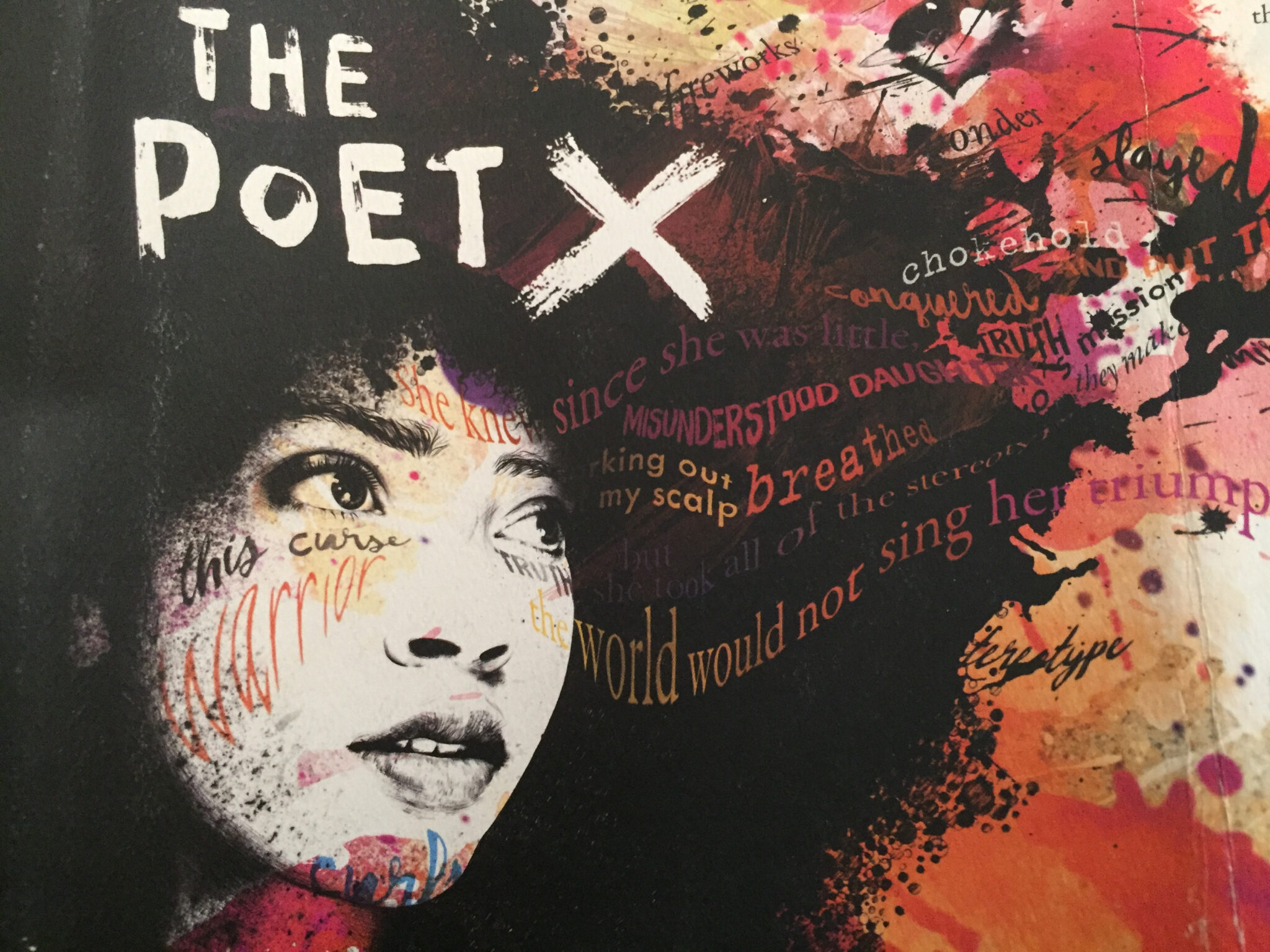

I was so excited to share with them an excerpt that I had read in Elizabeth Acevedo’s latest novel, “The Poet X.”

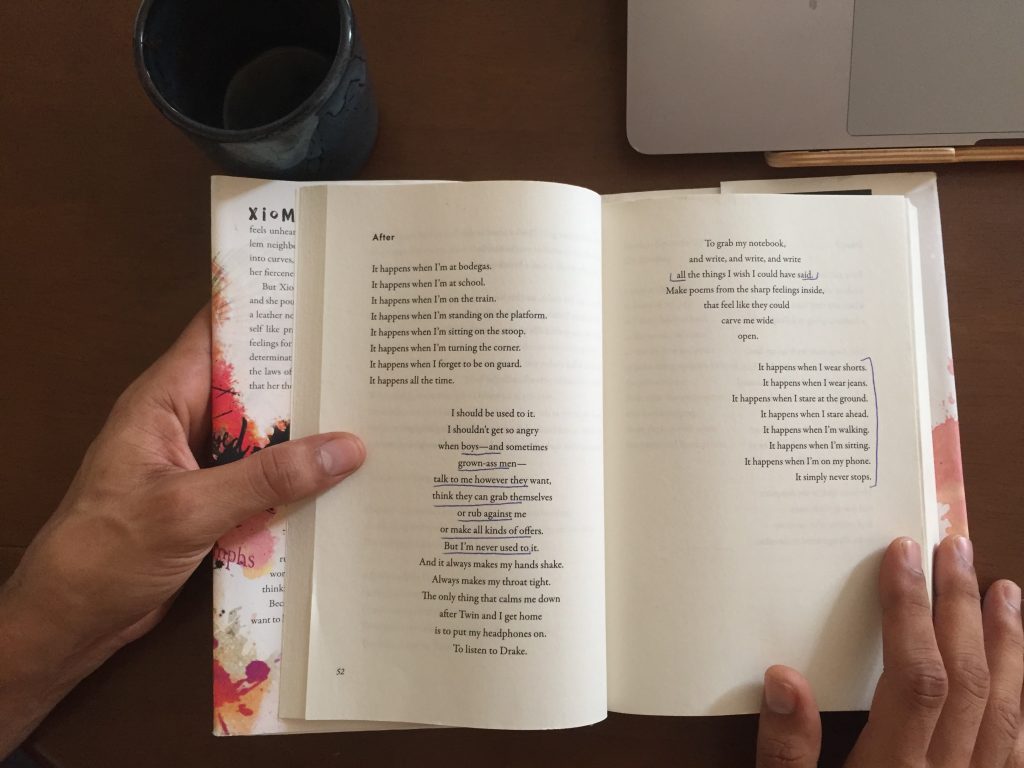

We read an excerpt from Part 1 of the novel, titled “After,” which described some of the protagonist’s experiences as a young Latinx teenager growing up and experiencing life in Harlem.

Part of Acevedo’s motivation in writing this novel was inspired by the 8th graders she’d taught in her career and the experience they frequently and collectively shared of not seeing themselves, their neighborhoods, or their experiences reflected in the literature they had been exposed to.

I was happy to see that my students, although representing Queens for life, were able to show to love to Harlem and were immediately immersed in Xiomara’s story, seeing themselves in her shoes.

*****SPOILER ALERT*****

If you have not read the “The Poet X,” by Elizabeth Acevedo, please continue reading at your own risk and take the opportunity to buy your copy and support Pan-African/ Latinx authors, artists, and the stories that are so often ignored and silenced.

Part of the excerpt, “After,” is a reflection from the protagonist, Xiomara, and her experiences of the violence perpetrated by our patriarchal society and sexist culture.

While I was sure that the young people in class would be able to relate to the story of Xiomara, I was more shocked than I anticipated to hear the young people’s reflection of the text and of their personal experiences and interactions with men in their lives.

Youth ages 14 – 17 shared experiences about men and elders’ unwarranted attempts at flirting with them, calling them out of their names, and at times whispering or yelling at them to provoke some kind of attention.

Some men would exclaim to their friends how the girls that they tried to flirt with were clearly underage, and would continue in the pursuit of engaging the young women in conversation. Others would follow them with their eyes, with comments, and often follow them down several streets.

In enclosed spaces like elevators, construction workers, co-workers or internship partners, would attempt to maintain an eerie sense of sociability that after a few days transitioned from unwarranted comments and conversations to being physically touched and grabbed non-consensually.

The young people shared that there were moments where they were supported and helped by allies, co-workers and at times parents. Their fear and concerns, however, grew larger in the moments where they were alone and without anyone to help them during these recurring situations. Many felt that just to speak out, call out the person, or resist against their aggressors or attackers, while alone, would have put them in unsafe, precarious, and dangerous situations where they would have been unable to defend themselves.

It was my intention for the young people to read a text that they could connect to, that was written in “their” voice, and that was relevant to them. However, I was not aware when I brought the prompt into class that I would feel so overwhelmed and shocked with the multitude of stories that these youth shared and wrote about regarding their experiences as young women facing these violences in their city, schools, and homes. I did not want to believe what I already knew so well, that at the ages of 13 – 14, my young women already had a slew of violent experiences and traumas that would continue to shape them as part of our culture and day-to-day routines. These same norms would also continue to guide the young men in our society and develop their rites of passage into a twisted manhood that simultaneously strips them of their humanity and gives them a power that celebrates the oppression of women, and the destruction of themselves.

These experiences are nothing new. Perhaps I was more shocked with my naive hope that the realities I grew up witnessing had become better for this generation. The reality is that I am still uncovering and unlearning the ways I have been taught to participate in a social morality that promotes power through trans and queer-phobia, misogyny, and sexism. As a heteronormative, cisgendered, light-skinned, english-speaking, United States born, university educated, and privileged man, I am not even slightly aware of the daily, life-long, constant and consistent terrorizing that women face and that we as men contribute to through our actions, conversation, humor, and our inadequacy to address these multilayered and complex issues within other groups of men including our friends, loved ones, co-workers, or strangers.

While I do not pretend to have the magical answer, I know that the solution begins with opening the conversation and exposing ourselves to the truths and lived realities of those impacted by what we have been taught to celebrate and glorify in our society. Oppression is something that we all inherently participate in, and the questions I would like to address are are not who is responsible or who can we fault, but how do we personally contribute to the issue and what are the personal choices we can make to unlearn and heal from the same patriarchy that has made us all victims to losing our humanity.

I was blessed as a young person to have met Elizabeth Acevedo when she was 14 years old at The Brotherhood/ Sister Sol in Harlem, NY. Elizabeth along with Frantz Jerome, a fellow member of The Peace Poets, invited me to join the space and the writing program they called The Lyrical Circle.

For years this was one of the few, if not the only safe haven that I had as a teenager, as I reminisce trooping from The South Bronx towards 96th street and heading uptown into Harlem. It was a space for me to explore and understand myself better and the world around me. It was a gift to hear Elizabeth’s poetry, rap, and music in those days, and have a better understanding of how she was impacted by our twisted ideas of manhood and how I had contributed.

My love for my sister brought a magnifying lens to my eyes that not only made me more aware, but made me want to strive to explore what I could do to make the world a more equitable, just, and compassionate place for all the women in my life.

Thank you Elizabeth, and thank you to all the women in my life who have helped me to be a bit more in touch with my own humanity– although a lifelong journey awaits me in unlearning the violences I have learned and that continue to attempt to shift me into the comforts of my privilege and power.

Spoken Word Poetry Writing Exercise for Educators

For educators and cultural workers interested in using this text as an entry point for youth to engage in conversation and continue exploring their lived experiences, I would like to offer the following prompts which I used to in class, based off of Acevedo’s text, to begin a 10 minute writing exercise that could be used to further the conversation:

It happens when… (3 mins)

It makes me feel like… (3 mins)

I wish I could have said… (3 mins)

Review and last thoughts (1 min)